Looking outward

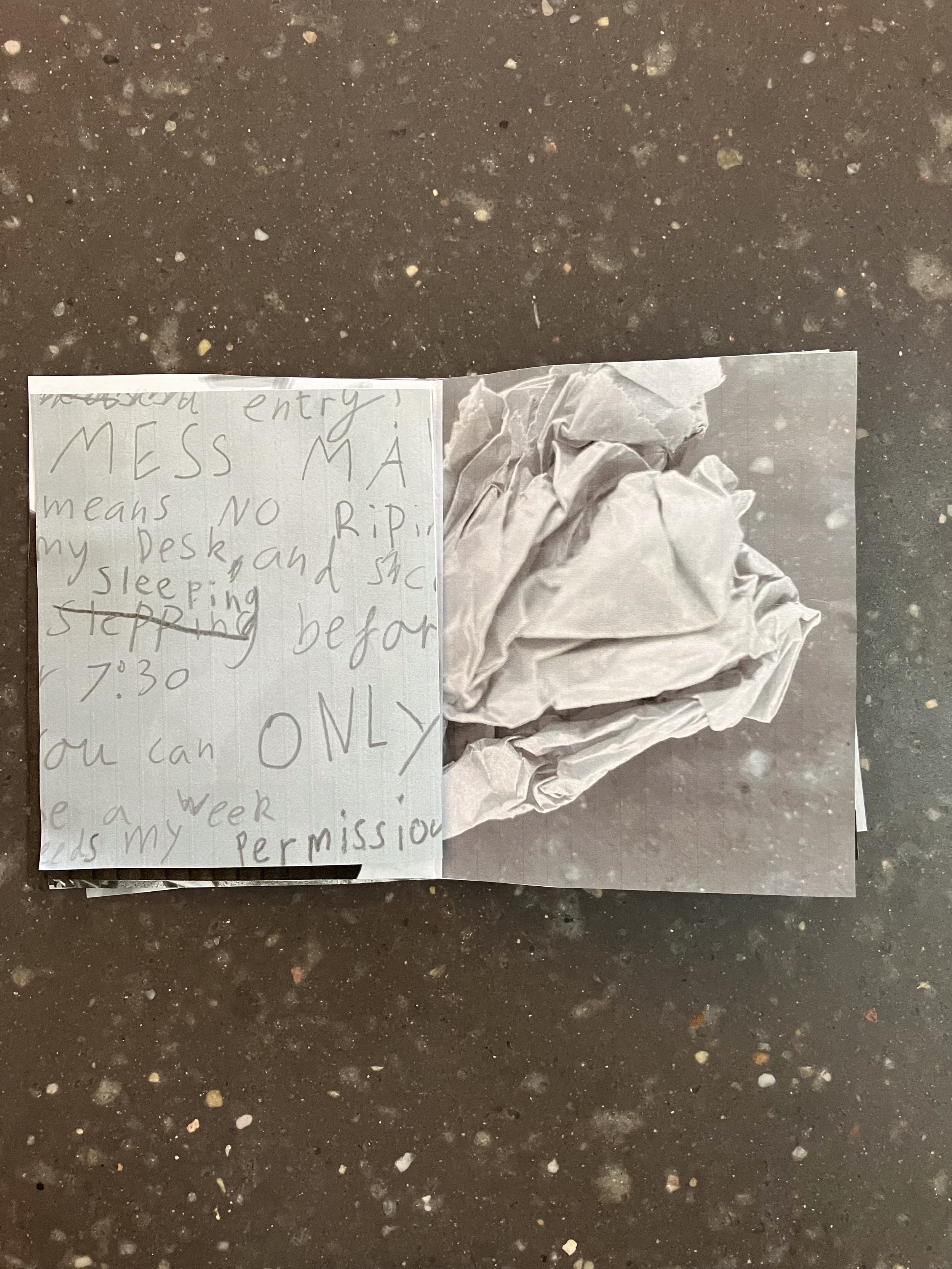

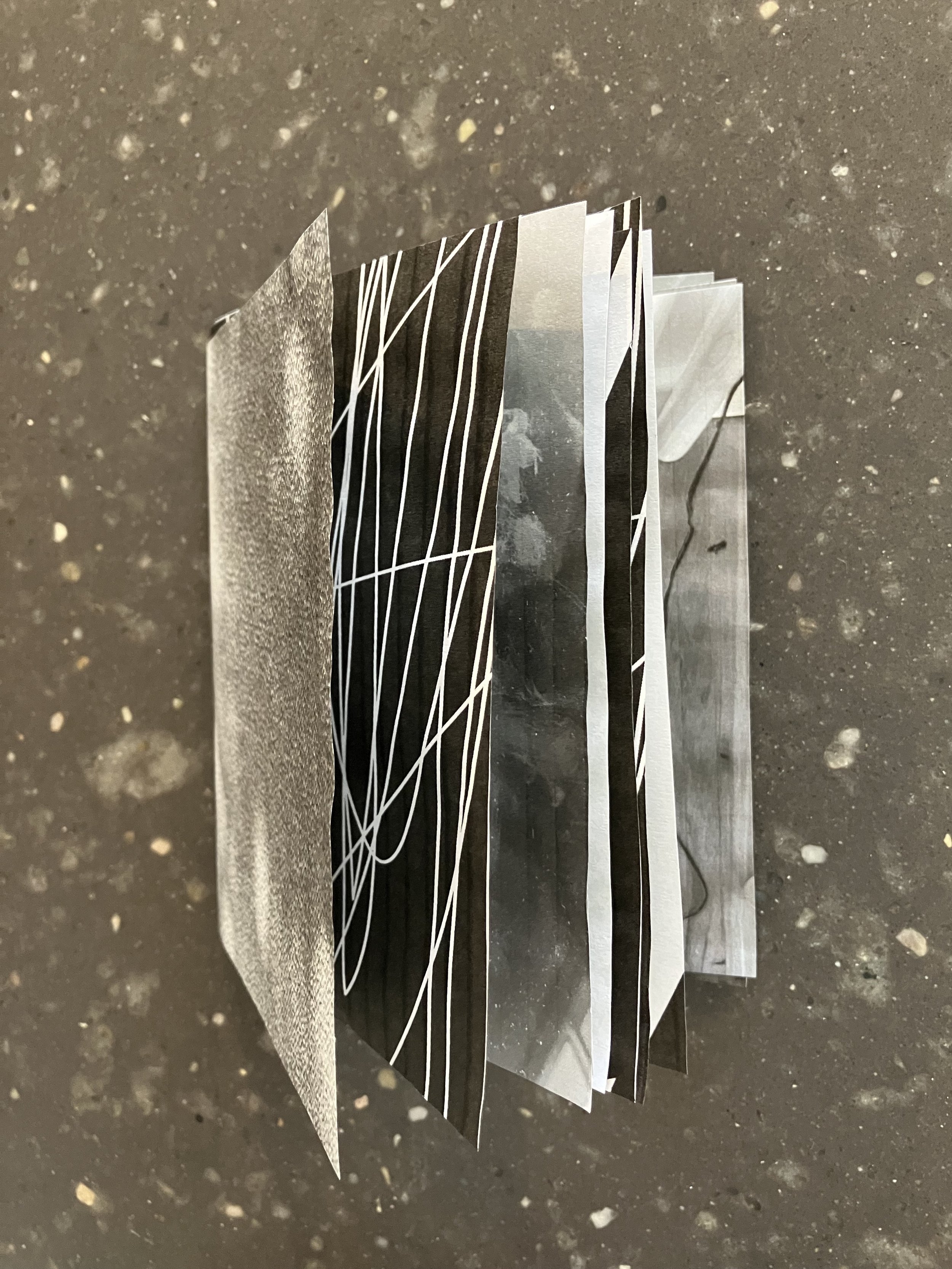

I wrote the notes below a few weeks into my masters (MPhil, ANU university). I was encouraged to position my work within the wider context of abstraction. I’d been prompted to think about whether my work was purely abstract expressionist or whether there were other methodologies at play. In order to examine this further I turned my focus away from the marks I was making from within and instead tried to find things in the world around me that could be a painting. I compiled these observations in a zine and wrote a little about automatism and mark-making.

Reflexive analysis

There are moments in an arts practice that require analysis. Blocks of time making work within an established process of production, reliant on techniques and understanding of material, and knowledge forged through repetition enable an artist to move forward in the studio. In order to study practice with clarity, pauses in production are necessary so that observations and ultimately connections and analysis can be carried out.

Positioning work at a particular point in time, within the far ranging and complicated spectrum of art-making is difficult. An important reason for this difficulty is the resistance of arts practice to conform to simple categories. Art history is complicated – artist borrow a little of this, and some of that. Breakthrough ideas that come to shape how groups of artists think and work can spring up simultaneously in different parts of the globe, lending flavour, methodologies and ways of thinking to others. Some might have a similar approach to their contemporaries but just call it by a different name.

Historical ways of understanding the world of art based on basic linear ideas of progress and time passing has of course been challenged. Works of art challenge and question the idea of history itself. Some have come to think of visual arts movements as a way of looking at how art intertwines and develops. Visual maps can work too. A hard line cannot be drawn between one movement and the next and that is the captivating thing about art – it resists definition – it squirms and rearranges against attempts to pin it down. This is why art is important because it remains vital, relevant to someone, somewhere, at sometime.

Understanding where work fits brings clarity. Even if it is a blurry territory between a bunch of other blurry territories. Even if the bounds of the practice extend across a variety of territories, stop briefly at some and intertwine with others. Knowing how an arts practice is similar to another, can be helpful when thinking needs to be flipped or de-centred, or indeed validated.

Automatism

Surrealism and the unconscious mind

Writer Andre Breton wrote his infamous Surrealist Manifesto in 1924. In it he leaned heavily on the ideas of Freud. He wanted to access the deep layers of the mind, places closed off and mine them for creative gems. He wanted to harness childhood, dreams and all things hitherto ignored or dismissed in the human brain. The search for the new, the unused and unexplored frontiers of the subconscious mind was the major preoccupation of the Surrealists, and was very much in line with the thrust of modernism – the insatiable thirst for newness – that characterised the twentieth century.

Freud used techniques such as automatic writing and drawing – marks and words elicited without planning or conscious thought – to access the unconscious minds of his patients. Surrealist artists adopted these techniques, tangling them with imagery from dreams and childhood to create art they believed transcended reality. Surrealist artists can generally be characterised by their work in one of two ways – to be influenced by the play of dreamscapes and strange twists on reality, or by abstraction through automatism.

Max Ernst employed Collage, Grattage (scraping) and grottage (rubbings) to create work that explored chance, distancing his own thoughts from his materials so that the decisions he made were veiled by the happenstance of his art-making processes. Spanish painter Joan Miro created paintings based upon an active dreamscape ‘ground’, over which he painted carefully drafted abstract symbols from his imagination mixed up with imagery from reality.

The throwing open of the unconscious mind brought about huge changes in the way people were making art and the Surrealists evolved abstraction through their exaggerated play on reality, courting the shock and disbelief of their audiences. The influence of this play is far reaching and ongoing. And extremely silly. It’s hard not to think of the Surrealists without seeing a certain obnoxious curly moustache.

Automatism as a concept with its associated spontaneity had emerged and by mid century became central to the work of abstract expressionists.

Abstract Expressionism

Automatism and gestural abstraction

Automatism was the core methodology of the Abstract Expressionist (Ab Ex) painters. Their process was performative, active and visible – their typically large works were not planned, instead the paintings found their form through the process of making itself. By drawing from the movement of their bodies and the deeper thoughts of their minds, by employing the visual language of their own gestures, and techniques reliant on chance, accident and memory. The Ab Ex painters invented their own brand of automatism.

Automatism methodology

Spontaneous, intuitive process

My paintings are unplanned. They often begin from the idea of something. Perhaps a colour I have lingering in my memory, a couple of loose forms that I’ve borrowed from a previous painting. Or they are recreations of other paintings where I decide to take a different fork in the road – paintings can be re-enactments of paintings I have already made but I choose the option I chose not to previously. Like sliding doors. Like a choose your own adventure novel.

Memory

I name the colours I create. Even if the colour red comes straight from the tube and already has a name – they say pimento I say tomato. I like to make colour collections though it is a pretty tight group and I enjoy being the gate-keeper deciding who can join. Nico Green is one of my favourites, it is a kind of staple, a friend to everyone.

I usually make small amounts of each colour, mixing new batches as I go, sometimes saving the dregs to use another day. I have a strong sense of what Nico Green is, its personality, its origin, when and how it can be applied. But each new batch is slightly different, this week I used slightly more yellow than normal, and perhaps a little less black so that it glowed a little more than last time. These changes don’t bother me. Actually, I enjoy seeing the little slippages as the colours falter from one day to the next. How I remember a colour to be is important, my memory is a piece of my creative machinery, quietly and surely influencing process.

Bored grey was an important colour for me in 2020. Denim Blue and Teapot Black are trending and Garage Pink often gets forgotten. I’ve started writing a kind of door list. Memory is a technique that belongs to automatism.

Gestural mark-making

Moving up to the canvas with a wet brush I decide at that moment what kind of mark I will make. The marks refer to nothing specific, but perhaps relate to a kind of subconscious appraisal, a bit more colour here, space there, a thicker line. Much of that decision making is worked out as I go, seeing how one layer interacts with another, how one mark detracts or obliterates something, the unexpected result of one colour touching another. I am interested in providing the opportunity for chance to play a role in the process. Without planning to directly, I like to set processes in motion so that they interact in ways I do not anticipate. These moments of interaction occur often in the happenstance of layering. At times I dial these chance moments up by pouring paint onto the surface allowing it to pool against placed objects. I scrape, rub, sand, pour and wipe the paint.